Healing-centered Engagement

Involves creating paths to wellbeing that are restorative by being empowering, community-oriented, and responsive to histories, cultures, and places.

Empowering

Moment-to-moment or across your life-span, consider what you and others need to feel empowered and liberated.

Culturally-informed and place-responsive

Develop awareness of your interconnectedness with place and with the land, as well as with your ancestral lineages and community histories.

Communally and politically-oriented

Taking action toward justice and fighting inequality lifts our sense of empowerment, meaning, and purpose.

Salutogenic and restorative

Salutogenic approaches to wellbeing focus on health rather than disease, and on restoring healthy forms of individual, cultural, and community identity.

Our goal at Windvane is not to tell you what it means to flourish or thrive, but rather to introduce some basic ideas and practices and encourage you to discover your own meanings. When we are exposed to other models of wellbeing, we are given some starting points for thinking about what makes the most sense for us. This section will introduce you to just a few of the many models and approaches you can learn from. Remember that you don’t need to retain all the information you see here – use what works for you, and leave the rest.

As your first assignment, we invite you to draw an image like the ones below that depicts what wellbeing means for you right now. Feel free to be creative – there are no right or wrong answers.

Models of Wellbeing

- U of T’s First Nations House Wellness Circle

- A Holistic Vision of Wellness, by the First Nations Health Authority

- The 5 Cs of Positive Youth Development

- 10 Domains of Wellbeing by Stanford WELL for Life

Indigenous Models of Wellness

“Mental wellness is a balance of the mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional. This balance is enriched as individuals have: PURPOSE in their daily lives whether it is through education, employment, care-giving activities, or cultural ways of being and doing; HOPE for their future and those of their families that is grounded in a sense of identity, unique Indigenous values, and having a belief in spirit; a sense of BELONGING and connectedness within their families, to community, and to culture; and finally a sense of MEANING and an understanding of how their lives and those of their families and communities are part of creation and a rich history.” – First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework

A great place to start learning more about Indigenous models of wellness is the Canadian Thunderbird Partnership Foundation’s First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework. Their 2015 report emphasizes how psychological wellness requires a harmony or balance of physical, emotional, spiritual, and economic health, and the use of culturally appropriate forms of Indigenous knowledge, practice, and language. Strength and resilience are the focus here, rather than deficits.

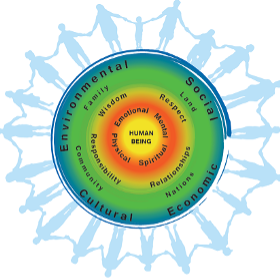

Take a look at a visual depiction of

a holistic vision of wellness developed by British Columbia’s First Nations Health Authority. The wheel shows the human being at the center, indicating that wellness begins with taking responsibility for our own health. The next

circle shows that wellness requires attention to physical, emotional, mental and spiritual dimensions of ourselves. Moving outwards, the next circle emphasizes the importance of respecting cultures and traditions, fostering wisdom

about language, tradition, culture and medicine, taking responsibility for ourselves and others, and promoting positive relationships. The next circle depicts how land, community, family, and nations are crucial components of our wellbeing.

And finally, the outermost circle indicates the importance of social, environmental, cultural and economic determinants of health. Around the image stand members of our community.

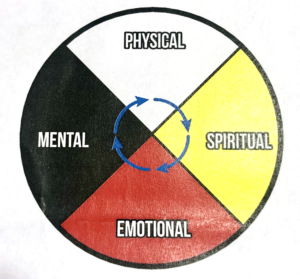

The circular image of a Medicine Wheel can be used in different ways to teach how interrelated topics or dimensions are interconnected. In Teaching by the Medicine Wheel: An Anishinaabe framework for Indigenous education, Dr. Nicole Bell explains how this Indigenous way of knowing the world can help us understand and envision how we are part of, or made of, a larger whole. Awareness of how we are made up of interconnected factors can lead to a more balanced approach to wellness. She explains that the Medicine Wheel teachings can help us see how:

“Indigenous people need to develop themselves, including their children, in a holistic way that addresses their spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental capacities, they need to address how to transmit learning through all of those personal aspects. The spiritual can be touched through ceremony, teachings, and stories. The physical can be transmitted through the land, while the emotional aspect can be developed through a balanced connection between the heart and the head. Mental capacities can be developed through ancestral languages and integrative learning.”

Anti-racist, Anti-oppression, and Decolonizing Models

There is so much research to show how racism has “multiple and pervasive impacts on well-being, self-esteem, and self-confidence” ( Corneau and Stergiopoulos). Our opportunities for health can be diminished by external forces of oppression and internalized beliefs coming from living under oppression. Sometimes it’s painfully easy to see these forces, and other times it can be hard to identify them and how they’re affecting you.

Anti-racist and anti-oppression approaches to health and wellbeing involve recognizing power imbalances and taking action to learn about and address how social, political, environmental or institutional systems perpetuate health inequities. Svetaz et al suggest that “We must start with ourselves to drive cultural and institutional changes necessary to achieve social justice. As individuals, we must examine our own beliefs, judgments, and practices (reflexivity) and acknowledge our social position and our roles in systems of privilege and oppression to understand how systems affect youth and families.”

Svetaz et al and

Corneau and Stergiopoulos present a framework for anti-racist and anti-oppression mental health care with seven main components: (1) Focus on activation. (2) Promote antiracism education. (3) Build alliance using participatory

processes. (4) Honor language that does not stigmatize. (5) Respect alternative healing strategies. (6) Practice advocacy, social justice/activism in parallel. (7) Foster reflexivity, for those who care and for those that are cared

for. This framework can be used at a community level, but you can also use these principles to shape your own path.

In terms of healing, many researchers advocating for anti-oppressive approaches favour “holistic” understandings of people, beyond strictly medicalized ones. Corneau and Stergiopoulos write about how the dominant biomedical approach to mental health tends to downplay or dismiss social or contextual factors, and moreover that it may emphasize a White view of “normal” health. Svetaz et al suggest that “Holism is, therefore, closer to a “social model” of mental “distress” than the dominant individualistic medical model of mental “illness”.” This can encourage us to investigate and try out various healing strategies beyond those of the dominant biomedical model. They write that “other holistic approaches to treatment may be included in an antiracist mental health services system—such as Indigenous practices that are rooted in balance, Chinese traditional medicine, Indian Ayurveda, African approaches, and yoga— to promote philosophies of healing that are responsive to the diversity of human experiences and worldviews.”

The literature review by

Corneau and Stergiopoulos point out some critiques of anti-racism and anti-oppression frameworks that we should think about. In particular, they explain how anti-racist framework has a limited ability to “conceptualize and differentiate

race, ethnicity, color, and culture as fluid constructs” and moreover that it can fail to recognize how racism “intertwines or intersects with sexuality, gender, class and other forms of oppression.” You may want to think about what

aspects of these frameworks support your growth, and what issues you might need to explore further. An alternate example is

Dr. Shawn Ginwright‘s model of healing-centered engagement, summarized above, which involves creating paths to wellbeing that are restorative by being empowering, community-oriented, and responsive to histories, cultures, and places.

In this model, the main cause of trauma should be found in one’s environment, rather than in an individual. This too is a framework that works both at a community level and also as something that you can work into your own personal

health plan.

To hear directly from BIPOC researchers, therapists, and patients on how racism and oppression can impact mental health care and what changes they recommend, check out the WORLD channel’s

Decolonizing Mental Health series, featuring 20 profiles of people addressing how our mental health care can be more responsive.

Concepts of Human Flourishing

Some researchers and institutions conceptualize their work using the word flourishing. Defining a “good life” has been a basic question across time and culture, fundamental to philosophy, religion, and ethics. The question is not only

how individuals can learn to flourish, but also what a flourishing society or world might look like. Not everyone uses the term “flourishing” – some thinkers have written about “thriving,” or “eudaimonic wellbeing,” for example, or

even “happiness.”

Roeser et al have proposed that there are three core ideas shared by scientific and traditional practitioners, namely: “(1) the idea that human beings have an intrinsic potential for positive change; (2) the role of practice and

community in the process of positive change; and (3) the interdependence between positive personal and social change.”

About Flourishing is a good place to get an introduction to some of these ideas. These authors emphasize the role of meditation or contemplative practices as key methods for developing skills of flourishing. They discuss how “contemplative

science seeks to understand how we can work with suffering skillfully and how we can see that at times our suffering has gifts to offer us.” Another key skill involves understanding the interdependence between our own wellbeing and

that of others. This essay is a product of a team of researchers who aimed to teach an undergraduate university course on “The Art and Science of Human Flourishing.” The essay gives an overview of the team’s study of models of flourishing,

wellbeing, or thriving, and how they arrived at their course’s model of student flourishing in “four main dimensions: (1) Awareness, (2) Connection, (3) Wisdom, and (4) Integration. These four dimensions of flourishing are explored

in detail through 11 more specific qualities of flourishing (e.g., focus, emotion, mindfulness, interdependence, compassion, diversity, identity, values, aesthetics, courage, and performance).” These dimensions are explored in detail

in this document, also in the context of other similar models.

Stanford’s Ten Domains of Wellbeing

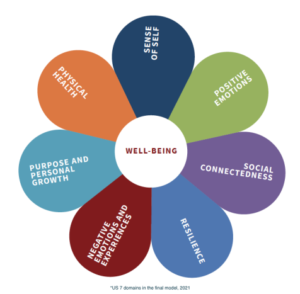

The Stanford University WELL for Life Survey, conducted during the pandemic, includes ten domains of well-being: social connectedness, lifestyle behaviors, stress and resilience, emotions and mental health, physical health, purpose and meaning in life, sense of self, financial security, spirituality and religiosity and exploration and creativity. This international study is offering insights into how different cultures perceive wellbeing, such that the petals of the flower pictured in their graphic depiction, shown above, may be smaller or larger depending on cultural context.

Mind-Body Therapies

For centuries, philosophers around the world have explored the question of how the mind and body are related. These theories have also shaped the field of psychology, with some researchers focused on the primacy of the physical body

and brain, others focused more on mental processes, and yet others taking a holistic perspective on how the mind and body interact. From the point of view of identifying and treating psychological distress, these theories have been

the basis for a range of “mind-body therapies.” You can read a concise and clear summary of these topics in Daniela Ramirez’s article,

Exploring the Mind-Body Connection Through Research, published on the Positive Psychology blog. Ramirez explains a mind-body theory of trauma, and she reviews a number of mind-body therapies, including meditation, hypnotherapy,

yoga, breathing, qigong and tai chi.

Learn More

References

Bryony Porteous-Sebouhian. Why acknowledging and celebrating the Black feminist origins of ‘self-care’ is essential. 27 October 2021. Mental Health Today.

Bundick, M. J., Yeager, D. S., King, P. E., & Damon, W. (2010). Thriving across the life span. In W. F. Overton & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), The handbook of life-span development, Vol. 1: Cognition, biology, and methods (pp. 882-923). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Corneau S, Stergiopoulos V. (2012). More than being against it: Anti-racism and anti-oppression in mental health services. Transcultural Psychiatry 49(2):261-282. doi: 10.1177/1363461512441594

Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., Ricard, M., & Wallace, B. A. (2005). Buddhist and psychological perspectives on emotions and well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science,14, 59–63.

Fernando, S. (2010) Mental health, race and culture. Macmillan International Higher Education.

Fiodorova, A., Farb N. (2022). Brief daily self-care reflection for undergraduate well-being: a randomized control trial of an online intervention, Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 35:2,158-170, Doi: 10.1080/10615806.2021.1949000

Harden, T., Kenemore, T., Mann, K. et al. (2015) The Truth N’ Trauma Project: Addressing Community Violence Through a Youth-Led, Trauma-Informed and Restorative Framework. Child Adolescent Social Work 32, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0366-0

Karina Zapata. Decolonizing mental health: The importance of an oppression-focused mental health system. Calgary Journal, February 27, 2020.

Larson, G. (2008). Anti-oppressive practice in mental health. Journal of Progressive Human Services 19: 39-54.

Lefley H.P. (2010). Mental health systems in a cross-cultural context. In A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. 2010: 135-161.

Maria Veronica Svetaz, M.D., M.P.H. Romina Barral, M.D., Ms.C.R. Michele A. Kelley, Sc.D., M.S.W., M.A. Maria Trent, M.D., M.P.H. Kenneth Ginsburg, M.D., M.S.Ed. Nuray Kanbur, M.D. (2020). ” Inaction Is Not an Option: Using Antiracism Approaches to Address Health Inequities and Racism and Respond to Current Challenges Affecting Youth“ Journal of Adolescent Health, Commentary, 67(3), P323-325, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.017

Prilleltensky, I. (2008). “The Role of Power in Wellness, Oppression and Liberation: The Promise of Psychopolitical Validity”. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(2), 116–136.

Prilleltensky, I., & Prilleltensky, O. (2006). Promoting well-being : linking personal, organizational, and community change. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley.

Ricard, M. (2006). Happiness: A guide to developing life’s most important skill. New York, NY: Little, Brown.

Robert W. Roeser, Abra Vigna, Brooke Lavelle, David Germano, John Dunne, Abigail Lindemann. On the Origins of the Art & Science of Human Flourishing Course’s Theory of Human Flourishing, by Student Flourishing Initiative Curriculum Committee.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141-166.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish : a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being (1st Free Press hardcover ed.). New York: Free Press.

Strengthening Community Connections: The Future of Public Health is at the Neighbourhood Scale

Sue Holdsworth & Emma Ash. From Trauma Informed to Healing Centered, from RECOVER Urban Wellbeing

Tew J. (2002). Going social: Championing a holistic model of mental distress within professional education. Social Work Education. 21. 143-155.

Vidya Shah, The Colour of Wellbeing: How do we ensure the wellbeing and success of BIPOC students and K-12 staff? EdCan Network, March 29, 2021

Image Credits

“The 5 Cs of Positive Youth Development,” ICAN, https://www.icanaz.org/the-5cs-of-positive-youth-development/. Accessed February 2022.

“The First Nations Perspective on Health and Wellness,” First Nations Health Authority, https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-for-first-nations/first-nations-perspective-on-health-and-wellness. Accessed February 2022.

“Ten Domains of Wellbeing,” Stanford WELL For Life, https://med.stanford.edu/wellforlife/research/stanford-well-for-life.html. Accessed February 2022.